Music from the Fault Zone — Historical Background

Mills College has always had a distinguished music program. In the 1870s the faculty

included Alfred Kelleher, a graduate from the Royal Academy of Music in London. Louis

Lisser, a pianist who studied at the Adademie der Kunst in Berlin, joined the faculty

in 1880 and served the college as Professor and Dean of Music until 1910. Under Lisser’s

leadership, the Music Department gained a national reputation; and the College named

its newly completed Grecian style music building in his honor in 1902. But by the

1920s, Lisser Hall no longer suited the rapidly evolving department; in 1926, in her

report to the Board of Trustees, Aurelia Henry Reinhardt, a social activist and educational

pioneer who served as the president of Mills from 1916 to 1943, recognized the building

of a “Department Center for Music” as the College’s highest priority.

Mills College has always had a distinguished music program. In the 1870s the faculty

included Alfred Kelleher, a graduate from the Royal Academy of Music in London. Louis

Lisser, a pianist who studied at the Adademie der Kunst in Berlin, joined the faculty

in 1880 and served the college as Professor and Dean of Music until 1910. Under Lisser’s

leadership, the Music Department gained a national reputation; and the College named

its newly completed Grecian style music building in his honor in 1902. But by the

1920s, Lisser Hall no longer suited the rapidly evolving department; in 1926, in her

report to the Board of Trustees, Aurelia Henry Reinhardt, a social activist and educational

pioneer who served as the president of Mills from 1916 to 1943, recognized the building

of a “Department Center for Music” as the College’s highest priority.

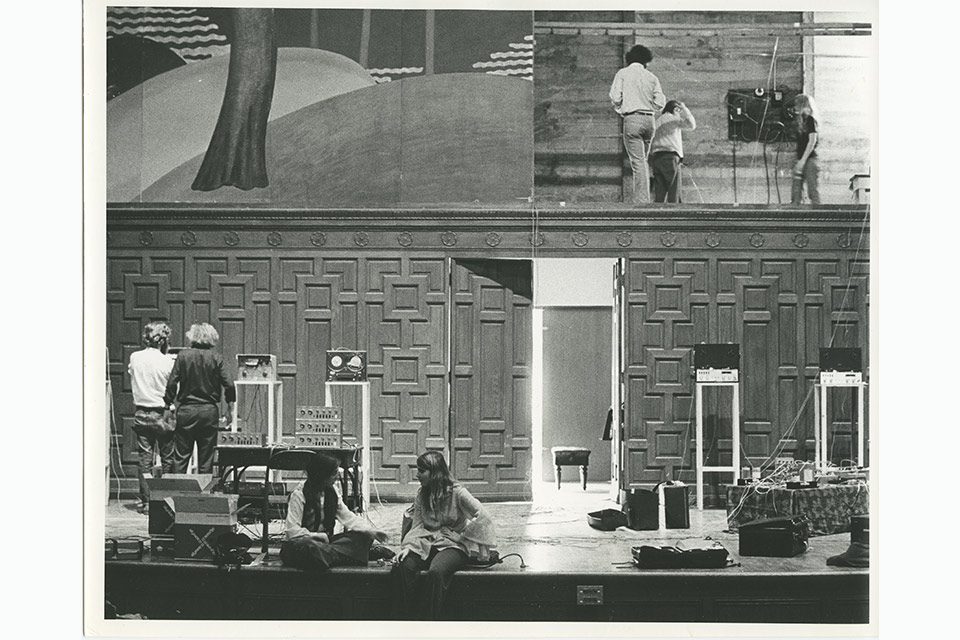

The Music Department rose to international prominence in the Music Building designed

by Walter H. Ratcliff Jr., which opened its doors in 1928. Its beautiful Concert Hall,

adorned by striking frescoes created by Berkeley artist Ray Boynton, featured performances

of new music in the 1930s and 1940s when the Pro Arte and Budapest string quartets

played works by Stravinsky, Cowell, Harris, Berg, Copland, Milhaud, Bartók, and Webern,

initiating a contemporary music performance tradition that continued in subsequent

years with the Mills Performing Group, the Kronos String Quartet, the Abel-Steinberg-Winant

Trio, and the Eclipse Quartet. French composer Darius Milhaud arrived at Mills in

1940, adding to the Music Department’s international reputation. Milhaud attracted

musical luminaries to Mills—such as Bela Bartók, Nadia Boulanger, and Igor Stravinsky—as

well as generations of talented students including a young pianist and composer named

Dave Brubeck. During the same period, composers Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and John

Cage taught at Mills. Together they forged an inclusive aesthetic attitude rooted

in an openness to and an active search for new sounds and musical forms, a unique,

characteristically “American,” musical identity recognized today as the experimentalist

tradition.

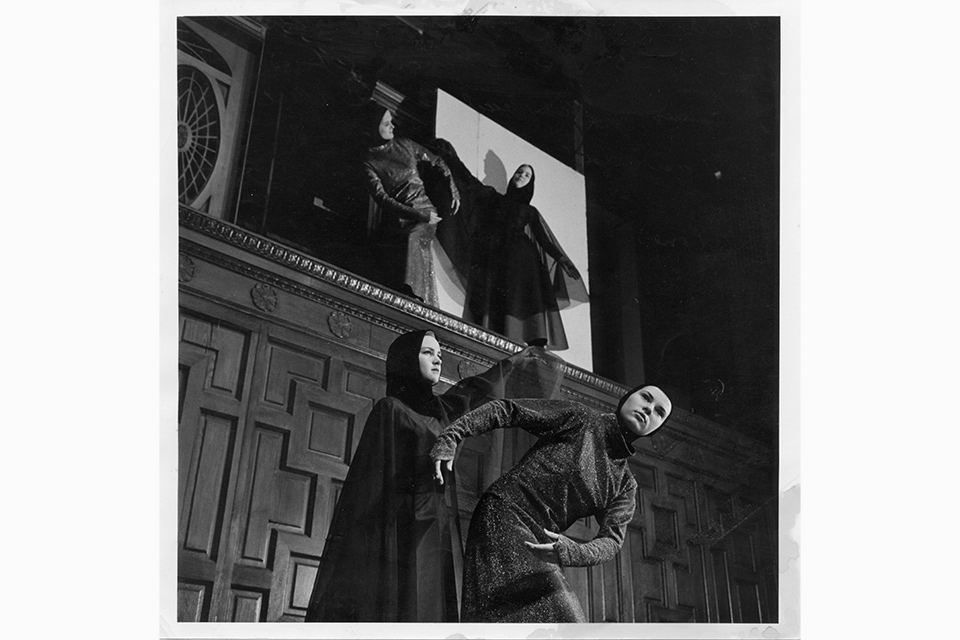

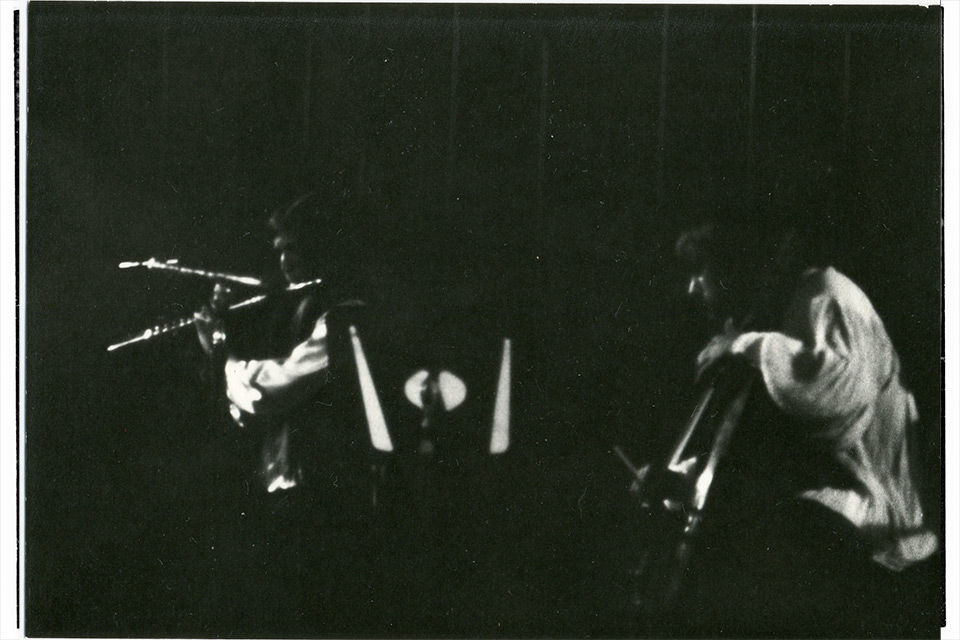

Noise was a crucial element of what Cage called the “all-sound music of the future;”

and percussion music was the first step towards this goal. The summer sessions from

1939 to 1941 featured a series of percussion music concerts, which established Mills

as a center for experimental music on the West Coast. On July 18, 1940 Cage and Harrison

presented a concert with staging and lighting by artists from the Chicago School of

Design, including the Bauhaus painter Lázló Moholy-Nagy, who were in residence at

Mills that summer. The concert was a great success, attracting enthusiastic reviews

not only from the local press, but also from Time magazine, placing Mills in a national

spotlight. Cage returned to Mills for another percussion music concert the next year.

The program included Horror Dream a new dance choreographed by Marian van Tuyl using

Cage’s Imaginery Landscape No. 1, a score for percussion, muted piano, and electronic

sounds produced by phonograph turntables playing test frequency recordings.

In the early 1940s, Cage spent a great deal of time writing letters and meeting with

potential donors to discuss plans for a Center for Experimental Music that would create

opportunities for musicians to collaborate with sound engineers in exploring musical

uses of electronic sounds. He presented his plan to Aurelia Henry Reinhardt, who enthusiastically

supported his application to the Guggenheim foundation for financial support. Although

Cage’s efforts were unsuccessful, his dream finally did become a reality in the fall

of 1966 when the San Francisco Tape Music Center moved to Mills, eventually becoming

the Center for Contemporary Music (CCM).

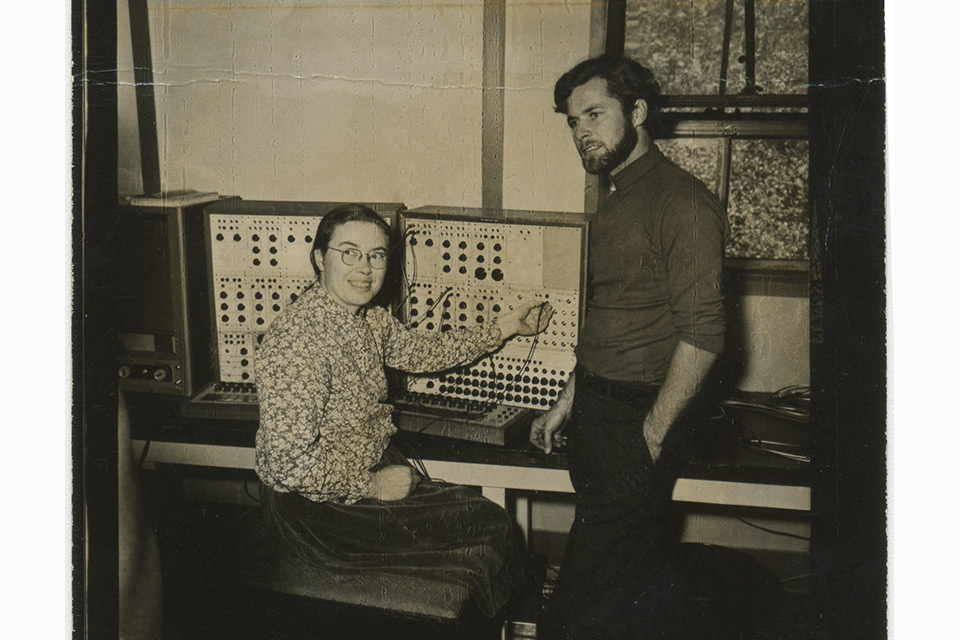

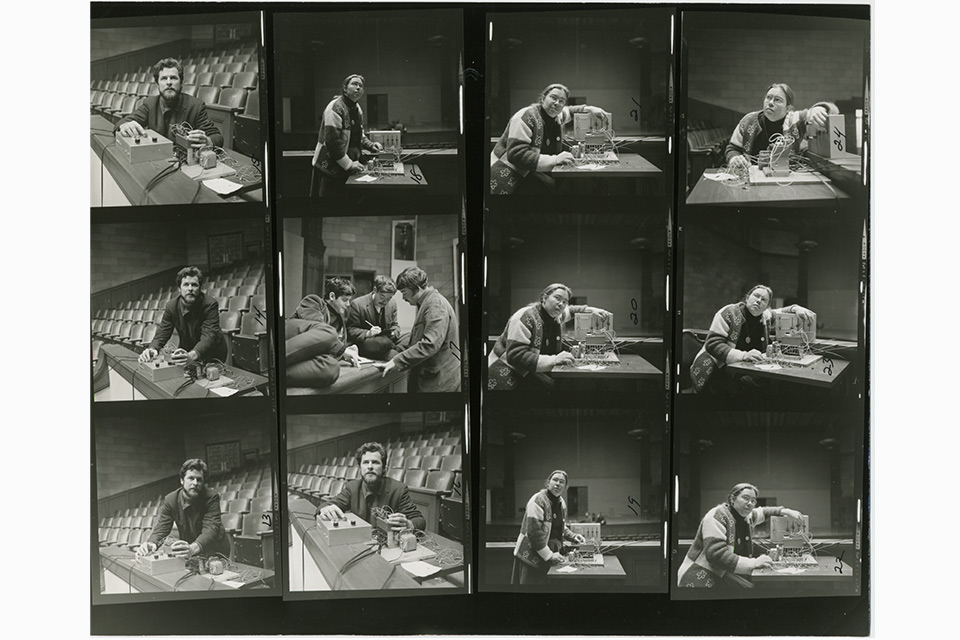

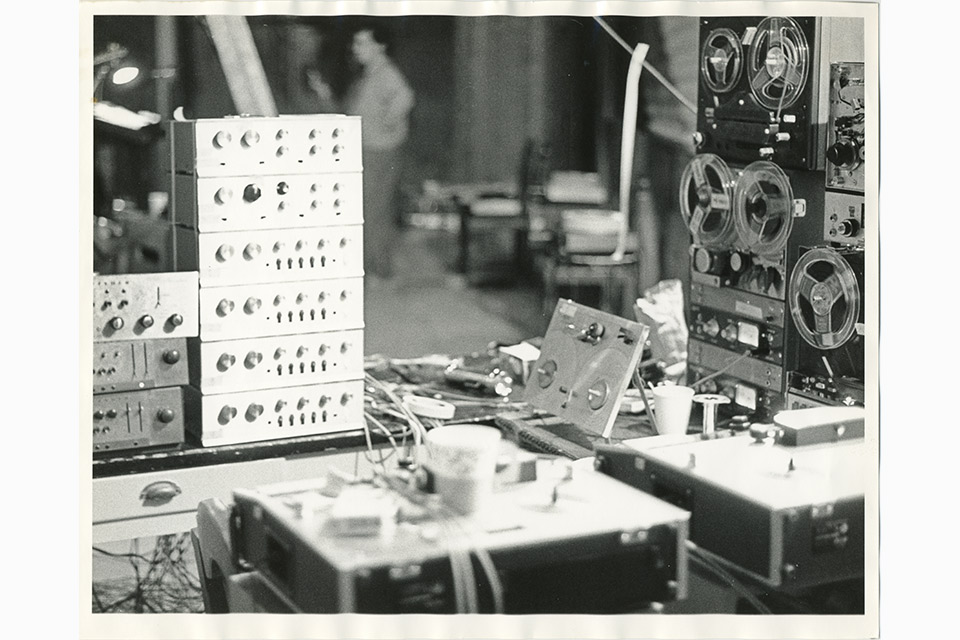

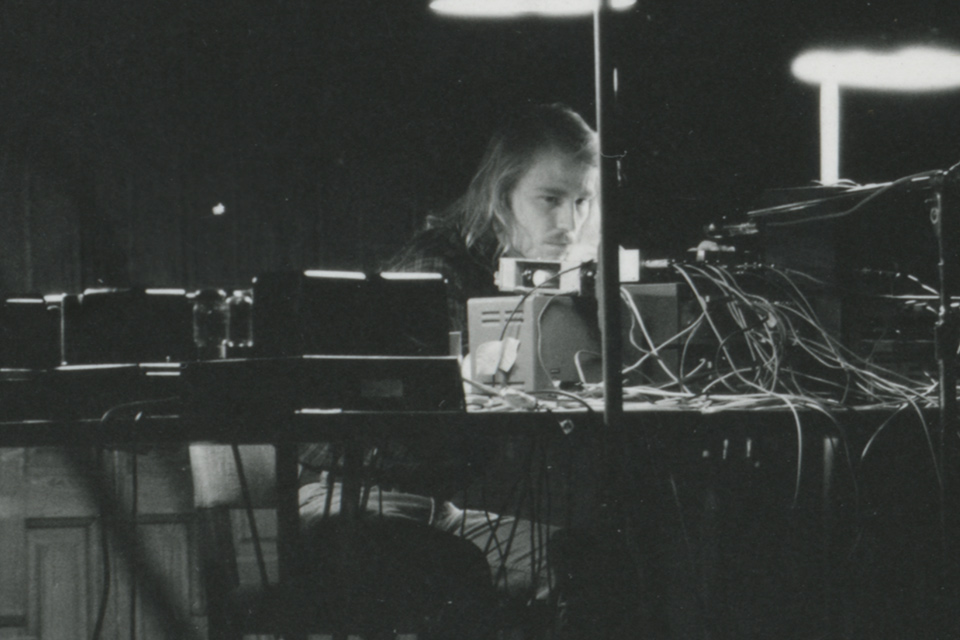

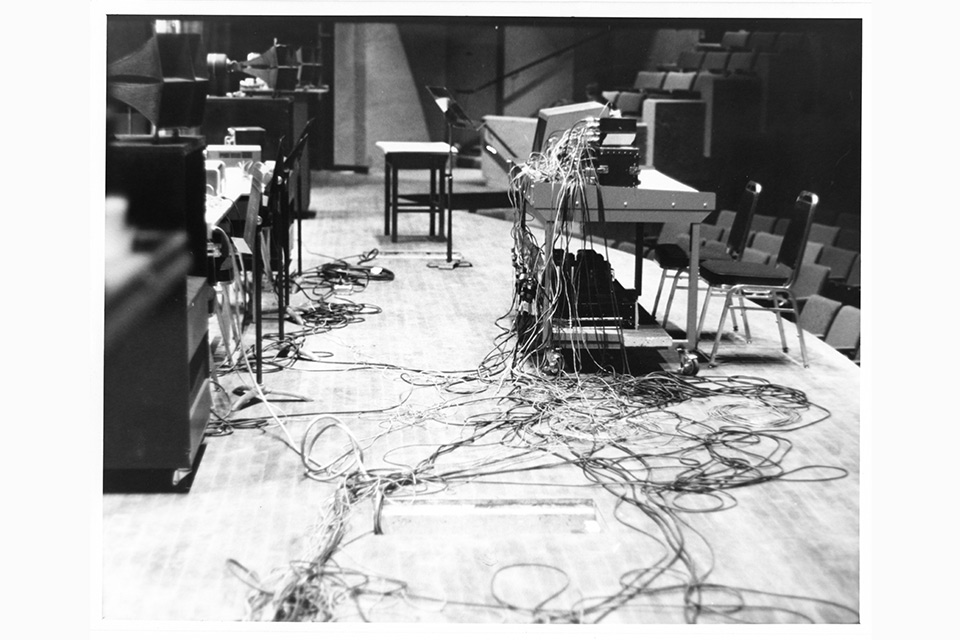

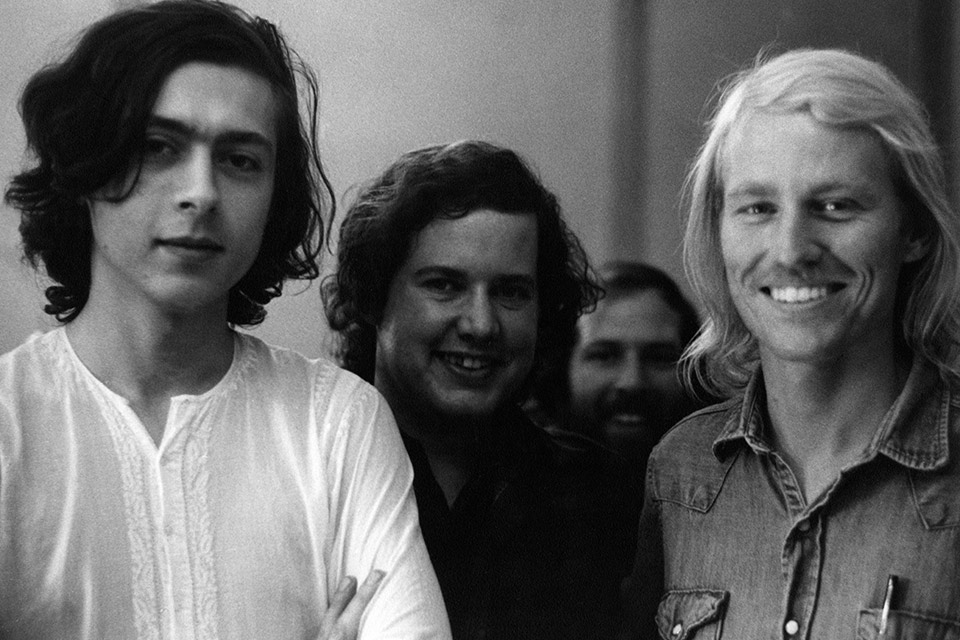

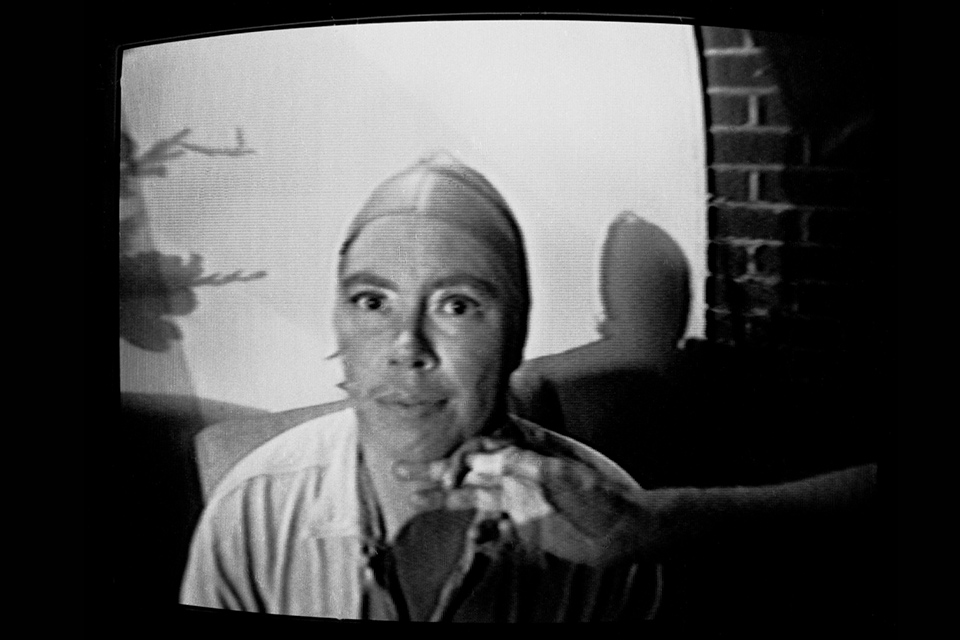

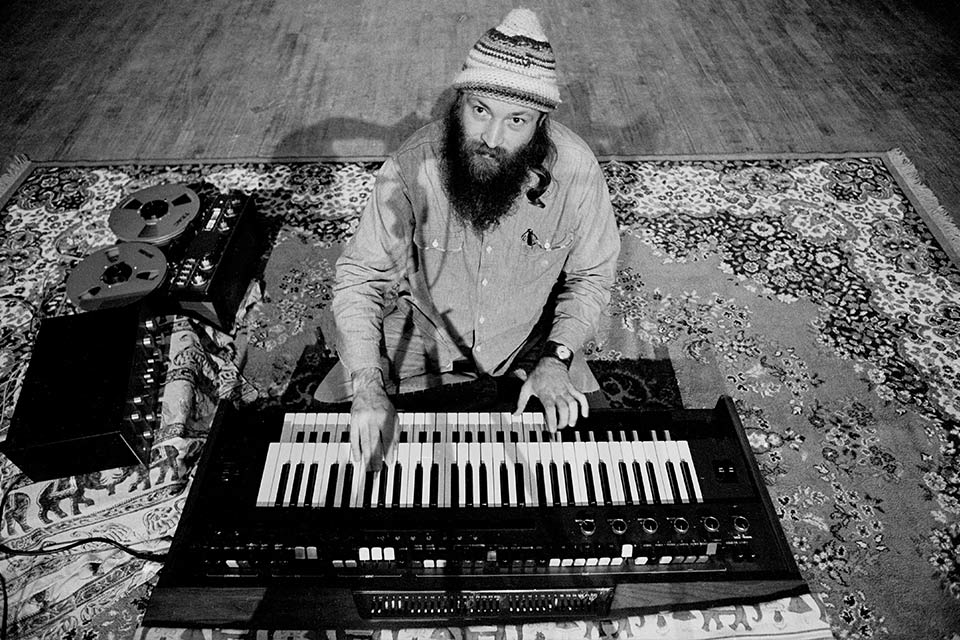

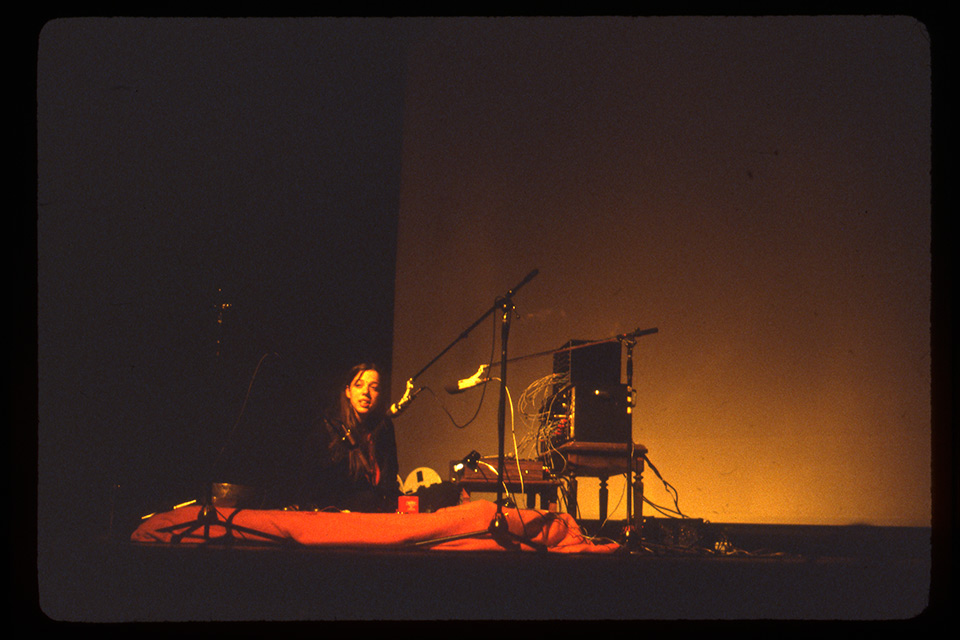

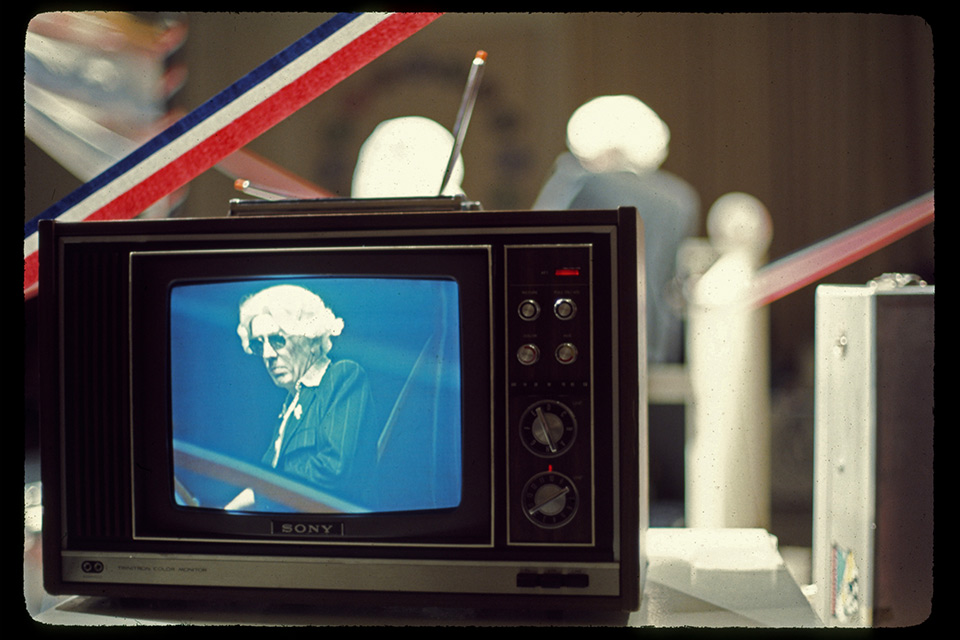

Composers at the Center for Contemporary Music developed a collaborative, interdisciplinary

approach to electronic music fusing visual, theatrical as well as musical elements.

Their innovative work quickly placed Mills at the forefront of the rapidly growing

field of electronic music. The aesthetic orientation of CCM has changed under a succession

of electronic music pioneers, including Pauline Oliveros, Robert Ashley, David Berhman,

David Rosenboom, and most recently Maggi Payne, Laetitia Sonami, Chris Brown, John

Bischoff, and James Fei. Over the years, composers at CCM have created multimedia

works with sound and light. They have played leading roles in the development of computer

music; created a new genre of experimental opera-for-television; designed new forms

of live electronic music and interactive works with acoustic instruments and electronic

media; devised musical artificial intelligence systems with computer music networks;

and have led the way in exploring musical interactivity on the internet, allowing

musicians from around the world to perform together in real time.

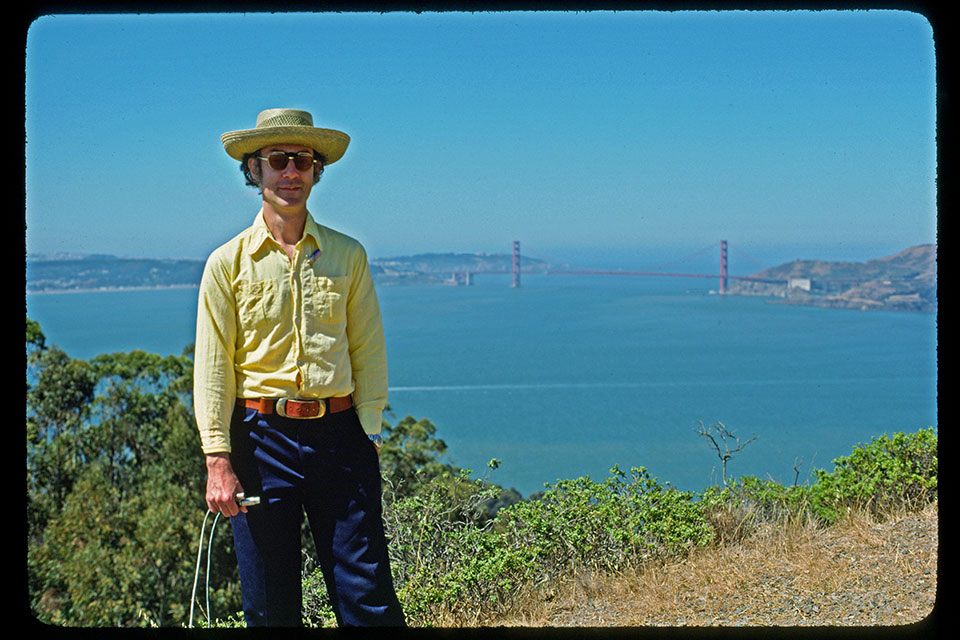

As the College’s reputation as a leading institution supporting musical innovation grew, creative artists from around the world joined the Music Department faculty, each uniquely contributing to Mills’s continuously evolving musical landscape. The list includes Annea Lockwood, Luciano Berio, Iannis Xenakis, Maryanne Amacher, Gordon Mumma, Alvin Curran, Morton Subotnick, Pauline Oliveros, Robert Ashley, Lou Harrison, Anthony Braxton, Alvin Curran, Christian Wolff, Wadada Leo Smith, David Behrman, Pandit Pran Nath, Annie Gosfield, Hilda Paredes, Joëlle Léandre, Terry Riley, Fred Frith, Maggi Payne, Chris Brown, John Bischoff, James Fei, Roscoe Mitchell, William Winant, Zeena Parkins, Tomeka Reid, and many others—a veritable Who’s Who in twentieth- and twenty-first century music history. Composers at Mills have played leading roles in the founding of musical minimalism; are advocates for the fusion of Western and Eastern musical traditions, and have incorporated cross-cultural influences from Java, India, Cuba, Mexico, and the Philippines into their compositions; their works and performance practices have crossed borders between rock and experimental music; they are free jazz pioneers; and on the cutting edge of new developments in contemporary music which explore relationships between written composition and improvisation.